Why Social Enterprise?

First Thing’s First:

Are they different? You’re not going to love this answer, but there isn’t a consensus here. Sometimes these terms are used interchangeably, sometimes they’re not. If we wanted to make a distinction, we’d say social enterprise is the use of business tools to address a social need, and social innovation is addressing a social need in a new, ground-breaking way. While it’s possible to use business tools without using them innovatively, and it’s possible to innovate without using business tools, we champion—and seek out—those working at the intersection of these two concepts.

For most people, “social enterprise” winds up being the (very broad) default term used to cover all of it. And as the term (and the movement itself) has gained traction over the last few years, its definitional parameters have been expanded to include just about everything mildly entrepreneurial and innovative but the kitchen sink. This is good in some ways, and not so good in others. Good, because it gets the message to a wide audience that there are ways to impact social or environmental issues other than the traditional nonprofit. Not so good, because it tends to lead the average member of society to assume that the biggest and loudest entities are the only (or even the best) social enterprise approaches.

Plenty of well-intentioned companies and ideas floating around in this space will tell you that they’re “changing the world” or “solving” their social problem of choice. But if they’re not addressing why people are poor in the first place, or why gaps in education continue to persist, or any number of other causal issues, the hard-to-swallow reality is, they’re not really solving anything. Performing charity, perhaps. But eradicating a social problem from the earth? Unfortunately, probably not. Indeed, the ventures that have garnered the most attention to date are only distant cousins to the social enterprises we seek foster. (For example, you’ve probably heard about a well-known shoe company that rhymes with moms). Don’t get us wrong, we love our cousins. But the degree of separation is a meaningful one.

For better or worse, the expansiveness of the term social enterprise that has snowballed its popularity (the bigger the bucket, the more stuff you can throw in there), has also led to trouble coming up with a definition everyone can agree on. Ask different people and you’ll likely get a different answer.

Definitions can include some or all of a number of concepts. Small nonprofits using entrepreneurial practices are on one end of the spectrum. Big mainstream companies simply doing business better (using environmentally sound practices, treating their employees particularly well, or donating a portion of their proceeds to pre-existing charities—often referred to as triple bottom line companies or conscious brands) on the other end of the spectrum.

In the middle you’ll find other definitions, spurring debate over aspects like the degree to which an entity’s primary activities must tie to its a social mission, the necessity of including social commitment in an entity’s formational documents, and whether a side project of an existing organization makes the cut. Yes, some definitions provide for overlap. And yes, it’s confusing.

Like most things in life, the portion of the vast social enterprise world that most resonates with you will depend on your experience and your objectives.

With all the murkiness and inefficiency that has come to surround defining social enterprise, articulating just what that portion is can be challenging. So, instead of adding more of the same, we’re inventing our own category. We call it non-nonprofit (that for-profit, mission-first stuff we were yammering about here). By carving out our own piece of social enterprise in this way, we are able to communicate more efficiently with our audience, connect with the right clients, and focus on what resonates most with us—entities created to solve deep-rooted social problems that can sustain themselves as for-profits.

Why Be a Non-Nonprofit?

The goal of our approach to forming and operating as a for-profit isn’t to make boatloads of money (although that would be a pretty good incentive to keep working harder and chipping away at the end to any number of social ills, don’t you think?).

The goal is simply to not be a nonprofit—to avoid the restrictions and burdens that are, by law or by culture, baked into the nonprofit framework.

Luckily, there are no rules on what types of entities you have to use to seek social change. We’ve simply been conditioned to believe that if you want to do good for the world, you have to start a nonprofit (or, at a minimum, go work for one). We’ve been told to believe that’s where all social good exists. The truth, however, is that simply is not (and does not have to be) the case.

Sometimes you have to crack open the mold to let the light in.

For those of you that have spent much time working in the trenches in nonprofit program implementation, you know. Nonprofits face many challenges. And contrary to popular belief, most people working in the nonprofit sector aren’t sustained for very long by rainbows and sunshine, or even pats on the back.

They’re fueled by a passion inside of them.

But when that passion is met with unreciprocated enthusiasm, mediocre resources (at best), and virtually no incentives to innovate or consistently perform at a high-level, many of the most promising social changemakers get burnt out, frustrated, and begin to wonder—is there a better way to do this?

In many cases? Why yes, there is.

While branding precision and transparency will be vital to gaining public support (don’t worry, we can coach you here too), operating as a non-nonprofit, in the most basic terms, is just a matter of paying taxes. The rest is all about how you create it. People can even still make donations to non-nonprofits if they want (albeit non-tax-deductible ones but—fun fact—the charitable tax deduction lure is irrelevant for anyone that doesn’t itemize on their tax return).

The point: where the venture can generate a steady stream of revenue, the freedom and undeniably exciting new possibilities that come with operating as a non-nonprofit entity far outweigh the taxes in the long run. If you can generate revenue through the use of a new set of tools, pay your taxes, and still wind up with more funds than you would’ve had otherwise to expand or improve your social program, the real question should be: why not?

Why Now?

Nonprofits are great for serving a community. But they are functionally designed to be agents of charity. This is a fact. They were conceived, and later codified into law, as a means of mitigating the amount of harm that exists as a result of social and environmental problems. Not solving the underlying problems in the first place. They’re also legally required to be dependent on public support (a real pain if you’re not into spending gobs of time making pleas for donations).

As the problems facing our country and our world get increasingly complex, and as social changemakers strive to meet this evolving need, the model itself has—counterintuitively—stayed exactly the same.

We can do more.

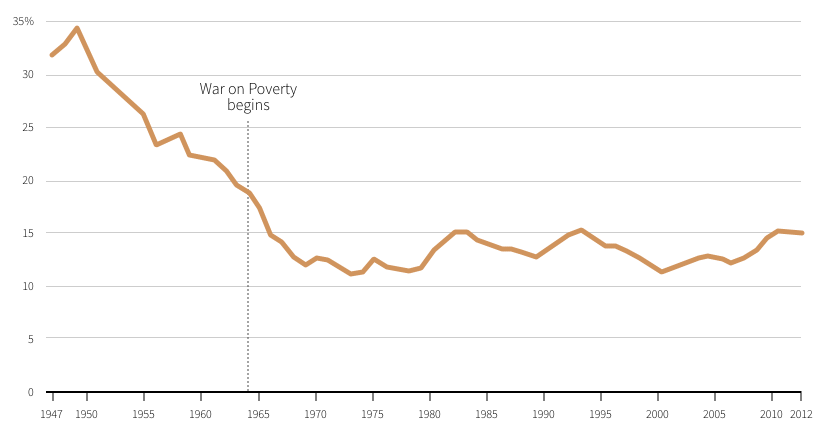

Question: How many social problems can you name that have been solved by nonprofits in the last 50 years? What about ever..? In case you’re wondering, the answer is zero. And by most metrics, they’re not even getting close.

It’s quite a rude awakening to acknowledge that the relative amount of social ill that exists today hasn’t changed much since the formalization of the nonprofit itself (our prescribed vehicle specifically for social change in this country, you guys). What does this tell us? That the model, combined with the culture and regulatory structure that has settled around it, isn’t effective at approaching the endgame (assuming, of course, your endgame is getting rid of a problem and not charity).

Let’s take a quick look at one example–the mack daddy of social problems, the one from which (arguably) many other social problems flow.

I know what you’re thinking. All things considered, at least that’s something (sort of?). But shouldn’t considerable manpower and resources channeled to accomplish a defined objective over 50 or 100 years do more than just something? Of course it should. Think about the impressive (remarkable! previously-not-though-possible!) strides that have been made in technology in even just the last 10 or 20 years. High speed internet, smart phones, smart cars and the like have completely changed our daily lives as we know them. COMPLETELY.

The difference?

Capital—human, financial, social, you name it. A culture where high-performance and innovation are rewarded. Freedom to test out new ideas without having to cater to donor wishes (donors who often understand very little about the complexities and underlying causes of the problems themselves).

All too often excuses are made for the nonprofit sector. And, unfortunately, the nonprofit sector’s limitations have led us to not only accept mediocre results, but to expect them. We think, “at least they’re doing something.” Something that by virtually any other standard would be deemed an incredibly inefficient use of resources.

The solution? Find another path.

Dream bigger. Do bigger.

It’s time to take some risks on something new. We recognize the problems are vast and the solutions are multifaceted. But the world needs more social problem solvers with the ability to shoot for the moon. The alternative is to stay right where we are.

Thanks

If you’ve made it this far, you’re our kind of person. Thank you for taking the time to learn more about why we do what we do. If we’re speaking your language, we’d love to hear from you! We’re always on the lookout for new partners, collaborators and fellow changemakers.

Action springs not from thought, but from a readiness for responsibility

Dietrich Bonhoeffer